“Safer at Home” far from home

A month ago, everyone in America’s life was upended by the COVID-19 pandemic. Students at the University of Wisconsin-Madison never returned from their spring break, and classes have remained online ever since.

Many students were scattered over the country in their hometowns. Others elected to stay at apartments in Madison they would be paying rent for anyway. But students from foreign countries studying at the University of Wisconsin did not have a choice.

Interstate travel is strongly discouraged and international travel is a near impossibility. Students intent on returning to their homes in other countries were suddenly stranded in Madison, sometimes a world away from where they’re from.

The housing situation has been relatively stable for most international students. Jeff Otieno, a sophomore and finance major from Kenya, has been staying safe and sheltering in place at his apartment in Madison, so little has changed for him as far as housing.

When in-person classes ended, most students in University Housing had to go home. International students in University Housing were the largest exception, and additional accommodations were made. “I think we have been fairly accommodated, especially due to the generous Emergency Aid,” said Farai Chinamo, a sophomore from Zimbabwe who lives in a residence hall.

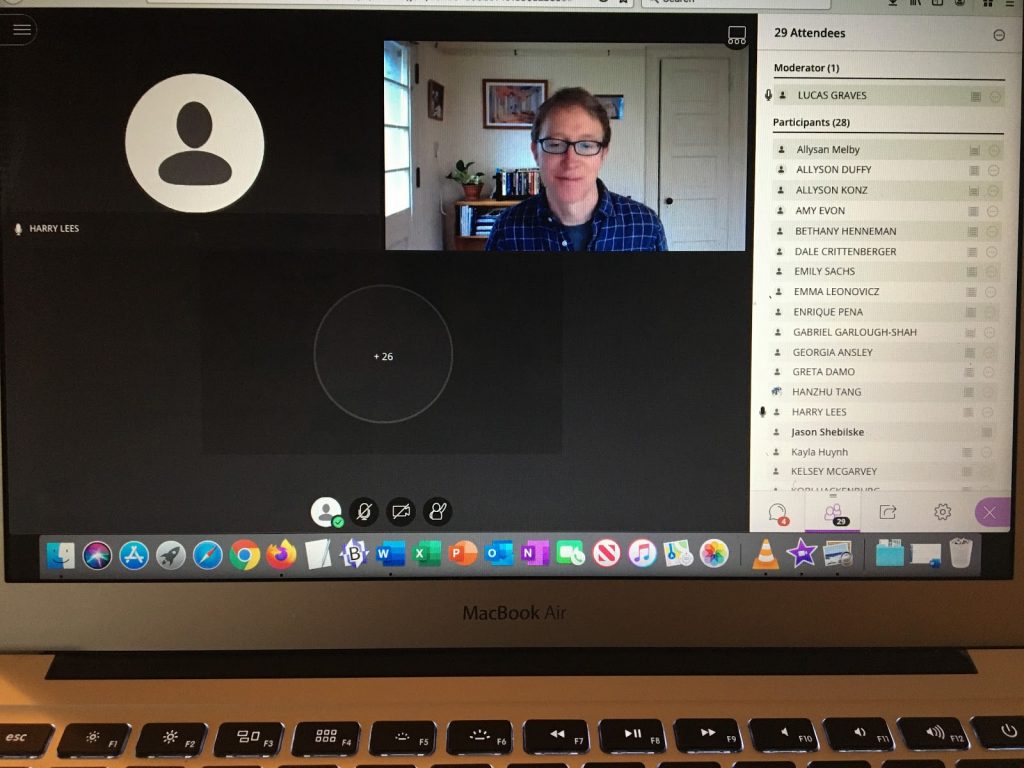

Critiques of the university lie mostly in the online education system. “In general, the university tried its best, but as for individual professors, some of them are just being really inconsiderate,” said Willie Zhou, a sophomore from Guangdong, China. It’s not all bad in his eyes, though: “I am quite enjoying the fact that I get to sleep more than 8 hours every day.”

Concerns lie largely with their families abroad. “I do worry [about my family,] but keeping in contact helps and knowing that they’re taking safety measures offers some comfort,” said Otieno.

Chinamo echoed this sentiment. “I worried for my grandmother and grandfather because they all have illnesses.” Being far from home is nothing new for international students, but it adds another layer of stress in an already uncertain time. “It’s been hard to think of the effect the pandemic is having back home,” Chinamo added.

Concerns over misinformation are also very real. “I am more worried about my grandparents than my parents because they always believe in rumors or false information spread on the internet,” said Zhou. “This would make them either downplay the virus or use the wrong way to protect themselves from the virus.” In a country hit hard by the virus like China, this can be especially dangerous.

International students also look forward to the day when travel restrictions relax. Like everyone, most cannot wait until travel restrictions are relaxed and we can all socialize more freely. “I’m really hoping I can spend more time out in the summer and hang out more with friends once it is safe to do so,” said Otieno. He even looks forward to hopefully seeing his family in Kenya later this year. Otieno is, “looking forward to possibly spending Christmas together if it’s safe then.”

Even visiting home when travel becomes possible again is not so simple though. “Monopoly and limited flights between China and the US really gave these giant airline companies opportunities to rip us off,” said Zhou. “Unless the market returns to normal or there is a mandatory evacuation paid by my government, I will stay in my bed.”

Many students feel isolated and separated from family during the nationwide shutdown but international students have the additional problem of being oceans away from family. Uncertainty abounds for us all in these times, and for international students the world can be that much more uncertain.